The state of New Jersey is currently executing a significant capital distribution event. It’s called the ANCHOR program—Affordable New Jersey Communities for Homeowners and Renters—and its function is to transfer a substantial amount of state revenue directly to residents as a form of property tax relief. The scale is notable. Last year’s iteration delivered $2.1 billion to approximately 1.8 million residents. The current cycle is on a similar trajectory, with over $2 billion earmarked for distribution.

On the surface, the mechanics are straightforward. The program is a tiered rebate system based on residency, income, and age. For the 2024 tax year, homeowners aged 65 or older with incomes up to $150,000 receive $1,750. Those in the same age bracket earning up to the $250,000 cap receive $1,250. The benefit for homeowners under 65 is slightly lower, at $1,500 and $1,000 for the respective income brackets. Renters are also included, receiving a flat benefit of $450, or $700 for those 65 and older, provided their income does not exceed $150,000.

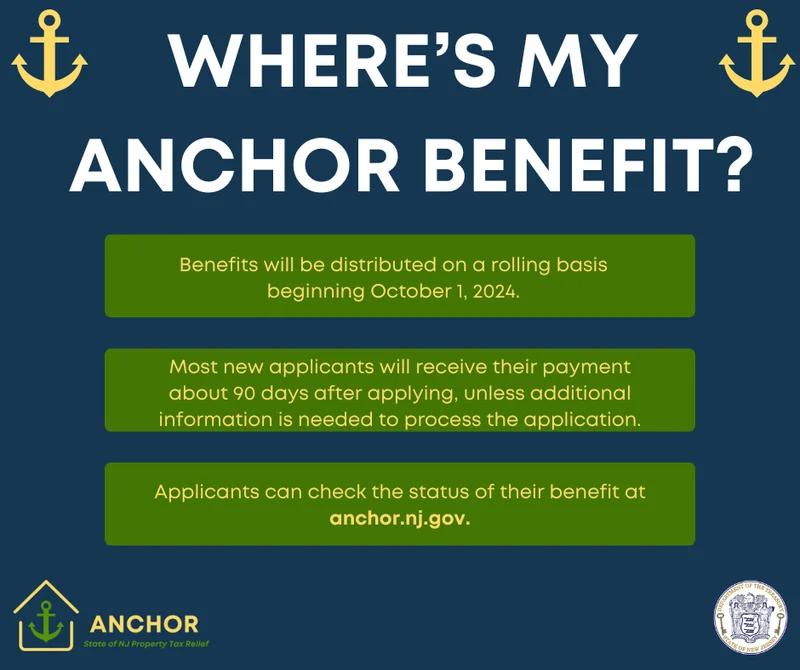

The state’s Treasury Department has been clear about its operational goals. Governor Phil Murphy stated, “Making New Jersey more affordable has been our mission from the start.” State Treasurer Elizabeth Maher Muoio echoed this, calling it a “straightforward program with a direct benefit.” To that end, the state has streamlined the process, automatically filing applications for about a million residents—to be more exact, over 1 million, based on prior-year data. The first payments began rolling out on September 15, 2025, with most applicants expected to receive their funds within 90 days of filing. This is, by any measure, a large-scale logistical operation.

More Political Asset Than Fiscal Policy

Anomalies in the Signal

This is where the clean narrative of a “simple and efficient” process begins to show some noise. My analysis of the publicly available source data reveals conflicting information regarding application deadlines. Multiple reports from the Treasury and associated news releases cite a firm deadline of October 31, 2025. However, other official documentation and FAQs extend this window to December 31, 2025. This two-month discrepancy is not a minor clerical error; it’s a significant variable for anyone attempting to access the funds. For a program predicated on simplicity, such a fundamental lack of clarity on its primary deadline is a material flaw.

Details on why this discrepancy exists are scarce. One could speculate it’s a rolling extension, but the lack of a clear, unified message from the state is a point of friction. It raises a methodological question: how can a program be measured as efficient if its core parameters are communicated inconsistently? Residents seeking to check their `anchor program nj status` online or by phone are met with a system designed for tracking payments, not for resolving fundamental timeline ambiguities.

This operational inconsistency becomes more interesting when placed against the political backdrop. The program is not operating in a vacuum. As New Jersey’s election cycle heats up, ANCHOR has transitioned from a fiscal policy into a key political asset. During a recent lieutenant governor debate, the program’s future became entangled with broader partisan narratives. The Democratic candidate linked the sustainability of state relief efforts to the "assault from the Trump administration," effectively nationalizing a state-level fiscal issue. Conversely, the Republican candidate, when pressed on funding, gestured towards the precariousness of taxing high earners who “are employing us.”

I’ve analyzed countless state-level fiscal programs, and the correlation between large-scale direct payments and election cycles is… predictable. The ANCHOR program fits this pattern almost perfectly. The messaging from the governor’s office emphasizes relief and affordability, which are potent themes for an electorate burdened by the nation’s highest property taxes. The `anchor check` itself (a tangible deposit or piece of mail) becomes a physical manifestation of a political promise fulfilled, arriving just as political messaging intensifies.

The central question then shifts from `what is the nj anchor program` to what is its primary function? Is it a sustainable instrument of fiscal policy, or is it a recurring, politically-timed stimulus designed to placate an overtaxed populace? The data suggests the latter. The program addresses the symptom—the pain of a large property tax bill—with a direct cash infusion. It does not, however, alter the underlying disease of New Jersey’s property tax structure. It’s a painkiller, not a cure.

This leads to the most critical unknown: `will nj anchor program be yearly`? The political debate indicates its future is far from certain. It is an expensive line item on the state budget, and its continuation is subject to annual budget negotiations and, more importantly, the political will of the party in power. For the nearly two million households receiving this relief (a significant voting bloc), the program’s perceived permanence could be a deciding factor. Yet, the state has made no long-term commitment. It remains a year-to-year proposition, its fate tied to the very political turbulence it is being used to navigate.

The program is, in effect, a massive, recurring expenditure that generates immense political goodwill. It provides genuine, necessary relief to millions. But framing it as a structural solution to New Jersey’s affordability crisis is a mischaracterization. It’s a transfer payment, and a very effective one at that.

An Exercise in Fiscal Anesthesia

The data is unambiguous: the ANCHOR program is a successful, large-scale wealth transfer from the state treasury to residents' bank accounts. It is also a brilliantly executed political instrument, timed to deliver maximum impact during a critical election window. It is not, however, a strategy for long-term tax reform. It is a recurring anesthetic, numbing the acute pain of New Jersey's chronic property tax condition without addressing the underlying pathology. The real question isn't whether your check is coming, but for how many more cycles this treatment can be administered before the fiscal reality requires actual surgery.

Reference article source: